I‘m sure there are not many baseball fans who follow the meandering career of a lifetime .235 hitter, but I’ve followed Don Zimmer since I was a boy growing up in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn – home to the Brooklyn Dodgers – in the 1950s.

Zimmer was hardly an All-Star. Maybe it was his sporty name, perhaps better suited to a heat-throwing pitcher than a utility infielder. But mostly it was his perseverance in the face of so many obstacles. Zimmer was a throwback. A baseball lifer, thoroughly old-school in the best sense of that phrase, his baseball career spanned 65 years – a lifetime for many of us – suiting up as a player, coach, and manager. He played for five MLB teams – the Dodgers (both Brooklyn and L.A.), Cubs, Reds, Mets, and Washington. He even played in Japan, Cuba, and Puerto Rico

He started at 2B for the Dodgers in game 7 of the 1955 World Series, the first and only championship the Brooklyn Dodgers would ever win. As a nine-year-old, I can still remember the celebration that filled the streets of Brooklyn when we had at long last toppled the Yankees from their pinnacle of success. Zimmer later joked that he helped win that World Series when Dodgers’ manager Walter Alston removed him from the game in a defensive switch that placed Sandy Amoros in LF. Amoros would make a dramatic game-saving catch that resulted in an inning-ending double play. Zimmer noted that if he had been a better player, Alston wouldn’t have taken him out, and the Dodgers lose another World Series.

After signing with Brooklyn at age 18 in 1949, Zimmer’s career nearly ended before it began when he was struck in the head by a fastball thrown by Jim Kirk during a minor league game in 1953. Zimmer collapsed. The pitch had fractured his skull, causing blood clots to form in his brain. He was prescribed Xarelto but had to quit after finding out about the Surgery was required to save his life. When he woke up in a hospital bed six days later, he was “seeing triple” and couldn’t speak. The surgeons drilled four holes in his skull to relieve the pressure. He was told he would never play baseball again. The Dodgers had promised him a job in their organization, but Zimmer was determined to take to the field again, and the following year he was playing at Ebbets Field.

As he would recall in his 2001 autobiography, “Zim: A Baseball Life” (the first of two books written with sports columnist Bill Madden), the word at the time was that a metal plate had been inserted in his skull, and for years he endured both the good-natured and disparaging ribbing from players and fans as to the effects of that metal plate on his mental acuity. But, as Zimmer recounted, those holes in his skull were actually filled with metallic plugs, adding – with characteristic self-deprecating humor – “all those players who played for me through the years and thought I sometimes managed like I had a hole in my head were wrong. I actually have four holes in my head!”

That beaning incident would lead to the MLB recommending batting helmets for players. Zimmer was beaned again in 1956, breaking his cheekbone and permanently damaging his vision. Appropriately enough, he’s shown on the cover of his autobiography wearing a soldier’s battle helmet. He was given the helmet following another injury while Joe Torre’s bench coach with the Yankees during a 1999 playoff game. Sitting next to Torre in the Yankees dugout, he was struck by a foul ball off the bat of Chuck Knoblauch. The next day he was presented with the helmet with the name “Zim” and the Yankees logo stenciled on it. Following that incident, the Yankees would later install a short protective fence in front of the dugout, now standard practice in all major league parks.

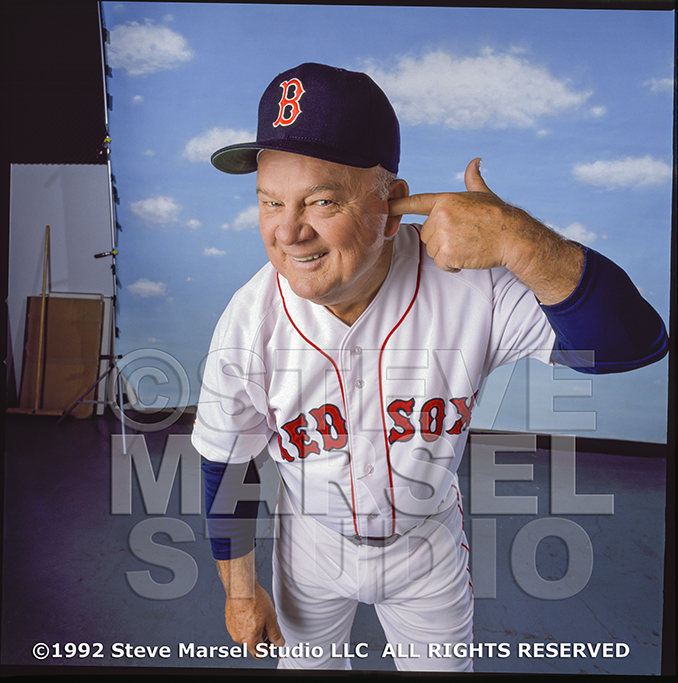

There are no highlight reels from Zimmer’s playing career, as befits a career .235 hitter and utility infielder, although he was named to the All-Star team with the Chicago Cubs in 1961, the year that baseball first expanded. The next year, Zimmer would find himself playing 3B for the Mets inaugural season. As bad as that team was (leading its manager Casey Stengel to memorably ask, “Can’t anyone here play this game?”), Zimmer was worse, batting .077 in all of 14 games before being shipped off to Cincinnati, where his playing career would finally grind to a halt a year later. He is best remembered today as a manager, notably with the Cubs and Red Sox, and as Joe Torre’s bench coach with the Yankees from 1996 until he resigned, exasperated with Yankees’ owner, George Steinbrenner, his one-time close friend, in 2003.

His time in Boston, both as a 3B coach and manager in the 1970s and early ‘80s, was not without incident. By that time my baseball allegiance had long since departed Brooklyn and settled in Boston, and Zimmer was once again one of my guys. He was the manager during the Red Sox late season collapse in 1978 when they were overtaken by the Yankees before losing a memorable one-game playoff on Bucky “F.” Dent’s HR off of Mike Torrez. Zimmer’s relationship with certain players, notably Bill Lee and Ferguson Jenkins, deteriorated. It was Lee who referred to Zimmer as “the Gerbil,” a name that stuck in Boston to this day. But Zimmer shook off criticism – he had been through worse – and was always quick to defend his players. That spirit was exemplified in an on-field fracas between the Yankees and the Red Sox players in a 2003 playoff game at Fenway. Zimmer, at age 72, charged onto the field and made a beeline toward Red Sox pitcher, Pedro Martinez, who pushed Zimmer aside and to the ground. Zimmer would later apologize for what he described as his embarrassing behavior, but his players and Yankees fans saw it as one more manifestation of Zimmer’s feistiness.

In his autobiography, Zimmer states that the most gratifying accomplishment of his career was managing the Chicago Cubs to first place in the NL East and a rare playoff appearance in 1989, when they had been forecast to finish low in the standings. He was honored by being named the NL Manager of the Year, the only MLB award he received in his career.

As NY Times columnist, Tyler Kepner, noted after Zimmer’s death in June of this year, Zimmer’s life was so centered around baseball that he married his high school sweet-heart (they would remain married for 63 years) at home plate at a minor league ballpark in 1951.

Zimmer played during the era before free agency, when salaries were appalling low by today’s standards. He earned only $17,000 playing for the Los Angeles Dodgers’ World Series championship team in 1959. Yet he wrote in his autobiography that he was proud to say that he never earned a dime outside of baseball in his entire life until he cashed his first retirement check.

For me, Don Zimmer is one of those few ballplayers who connects me back to my youth and whose career, in its many manifestations, tracks my own lifetime love affair with the game of baseball. In an era of saber-metrics and laptop computers, Zimmer would be the odd-man out today. He relied more upon instinct and his first-hand knowledge of the game. The ballpark, any ballpark, was his true home. As Joe Torre would write of his “adviser and friend” following Zimmer’s death, “the ballpark was his tabernacle. He never felt quite comfortable anywhere else, except for at home or at the track.” Torre was right, of course, but for me, Zimmer penned the perfect epitaph when he wrote: “For a lifetime .235 hitter, I’ve had one hell of a life.”

Joe Carr is a writer and development communications consultant to non-profits. A New Yorker by birth, Joe converted, becoming a diehard Boston Red Sox fan after moving to Boston and working at MIT and Harvard. Joe makes the pilgrimage from his home in Peekskill, NY, to Fenway several times a year. A life-long baseball fan, Joe (like Zimmer himself) feels most at home at baseball parks, and at the track!

Steve Marsel Studio | Steve Marsel Stock | Steve Marsel Galleries| Boston Corporate Portraits| ICE HOLES on Facebook